Peripheral neuropathy is nerve damage caused by chronically high blood sugar and diabetes. It leads to numbness, loss of sensation, and sometimes pain in your feet, legs, or hands. It is the most common complication of diabetes.

About 60% to 70% of all people with diabetes will eventually develop peripheral neuropathy, although not all suffer pain. Yet this nerve damage is not inevitable. Studies have shown that people with diabetes can reduce their risk of developing nerve damage by keeping theirblood sugar levels as close to normal as possible.

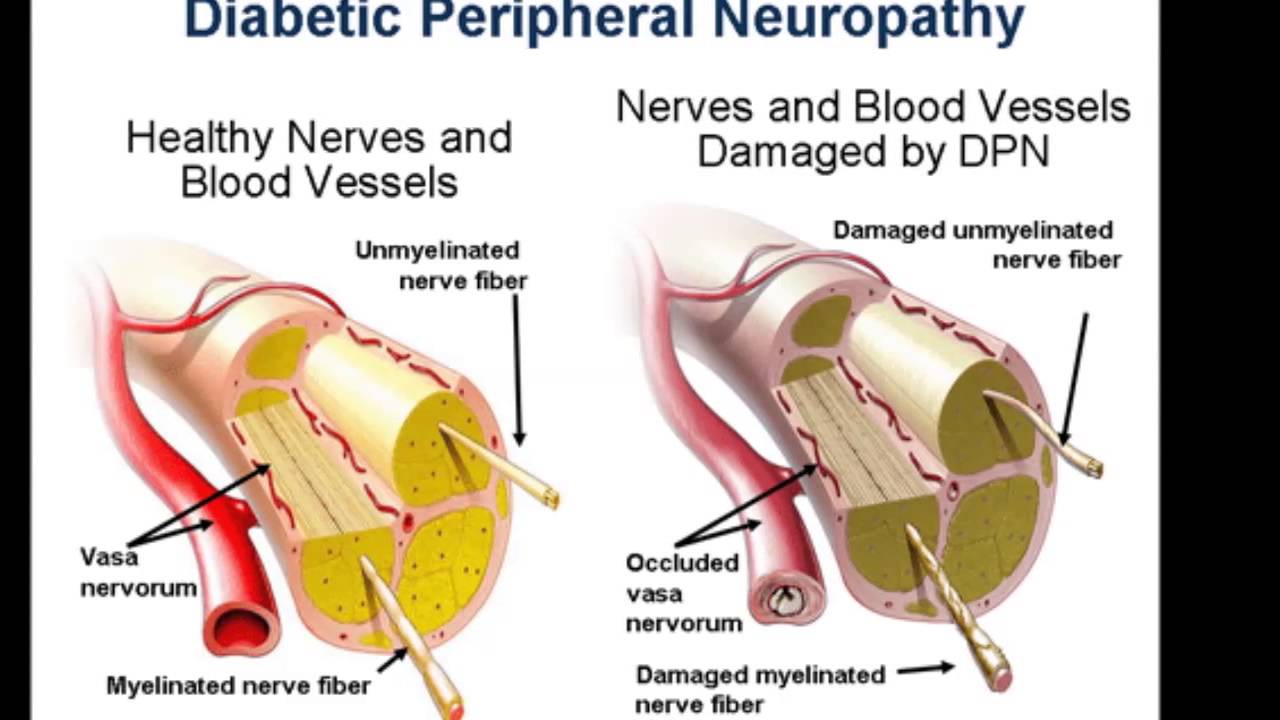

What causes peripheral neuropathy? Chronically high blood sugar levels damage nerves not only in your extremities but also in other parts of your body. These damaged nerves cannot effectively carry messages between the brain and other parts of the body.

This means you may not feel heat, cold, or pain in your feet, legs, or hands. If you get a cut or sore on your foot, you may not know it, which is why it’s so important to inspect your feet daily. If a shoe doesn’t fit properly, you could even develop a foot ulcer and not know it.

The consequences can be life-threatening. An infection that won’t heal because of poor blood flow causes risk for developing ulcers and can lead to amputation, even death.

This nerve damage shows itself differently in each person. Some people feel tingling, then later feel pain. Other people lose the feeling in fingers and toes; they have numbness. These changes happen slowly over a period of years, so you might not even notice it.

Because the changes are subtle and happen as people get older, people tend to ignore the signs of nerve damage, thinking it’s just part of getting older.

But there are treatments that can help slow the progression of this condition and limit the damage. Talk to your doctors about what your options are, and don’t ignore the signs because with time, it can get worse.

Drugs associated with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

Painful neuropathy is a common and disabling problem in patients with longstanding diabetes mellitus. Tricyclic antidepressant drugs and other chronic analgesics have been beneficial in some patients,1 but no agent successfully relieves pain in most patients and adverse effects often preclude their use in high doses. Anecdotal reports suggest that gabapentin ameliorates pain associated with neuropathy and other neurological conditions with few side effects.2 3 We conducted a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial to study the effect of low dose gabapentin in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy.

We recruited 40 patients with painful diabetic neuropathy who had (1) diabetes for at least 6 months on a stable dosage of insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agent, (2) distal symmetric sensorimotor neuropathy as shown by impaired pin prick, temperature, or vibration sensation in both feet and absent or reduced ankle reflexes, and (3) daily neuropathic pain in the acral extremities, of at least moderate severity, for over 3 months that interfered with daily activity or sleep. Excluded were those with diabetes and chronic renal insufficiency, painful diabetic plexopathy, or lumbosacral polyradiculopathy, peripheral vascular disease, another painful condition, or other cause for neuropathy. Patients were randomly assigned to gabapentin (300 mg capsules) or placebo for 6 weeks (phase I) followed by a 3 week washout period and then crossover (phase II). The dose of gabapentin or placebo was increased by one capsule every 3 days to a stable dosage of one capsule three times daily (900 mg/day) that was maintained throughout the remainder of the treatment period. The low dosage of gabapentin was chosen to minimise adverse effects that might compromise blinding. Treatment with stable dosages of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents or narcotics were permitted during the trial but patients discontinued all other chronic analgesic medications 3 weeks before study entry.

At the beginning and end of each treatment period, patients rated their level of pain over the preceding 24 hours on a 10 cm visual anologue pain scale (VAS), ranging from 0 (“no pain”) to 10 (“worst pain ever”). Present pain intensity (PPI, “rate how much pain you have at this moment,” using a similar 0–10 scale) and the McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ) were recorded at the initial and final visits of each treatment period.4 At the end of each treatment period patients provided a global assessment of pain relief: none, mild, moderate, or excellent, as compared with the level of pain preceding each treatment period. The global assessment of pain relief was dichotomised (none/mild vmoderate/excellent) for purposes of analysis. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at St Elizabeth’s Medical Center and all patients gave written informed consent.

There were 31 men and nine women, with an average age of 62 years (SD 10.9 years, range 43–82 years). All but one had adult onset diabetes mellitus, with a mean duration of 14 years (SD 9.9 years, range 6 months-40 years). Ten had neuropathic pain limited to the feet, 19 had pain in the feet and legs, and 11 had pain in the feet, legs, and hands. The mean duration of neuropathic pain was 4 years (SD 3.5 years, range 4 months-15 years). Twenty five had previously used narcotics or other chronic analgesics to manage their pain.

Nineteen patients were randomised to the active drug and 21 to placebo during the first treatment period. The mean reduction in the MPQ score was 8.9 points with gabapentin compared with 2.2 points with placebo (p=0.03, two sample t test). There were no differences in the mean change of the VAS or PPI scores between gabapentin and placebo (table). Fourteen patients reported moderate or excellent pain relief with gabapentin only, six with placebo only, and three with both; 17 reported none or mild relief after both treatments (p=0.11, McNemar’s test). There were no serious adverse events. Adverse effects were significantly more common with gabapentin (12 patients) compared with placebo (four patients, p<0.001, McNemar’s test). The most common side effects of gabapentin were drowsiness (six patients), fatigue (four), and imbalance (three). All adverse effects resolved promptly after discontinuation of the drug.

Comparison of mean change in pain scales between gabapentin and placebo

Anecdotal reports suggest that gabapentin has beneficial effects in patients with various painful neurological conditions, including HIV neuropathy,2 postherpetic neuralgia,2 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.3 The mechanism of action of gabapentin in ameliorating pain is unknown, but animal studies suggest that its pain modulating properties may be linked to the release of the neurotransmitter GABA in spinal cord pathways that modify pain perception.5

There was statistical improvement in only one of four end points, the MPQ score, with gabapentin compared with placebo. The MPQ is a valid, consistent, and reliable measure of subjective pain experience, and usually correlates with other measures of pain intensity, including the VAS and PPI scales.4 We designed the study to have an 80% power to detect a 20% reduction in pain scores, reflecting a modest but clinically important improvement.

The mean change of the VAS and PPI scales and the patient’s global assessment of pain relief were not significantly different from placebo. We used a crossover design because of its statistical efficiency, but the MPQ and VAS scores did not return to baseline after crossover in patients who received gabapentin in phase I (the washout period was inadequate); therefore, we may have underestimated improvement with gabapentin in the VAS scale that may have been detected using a parallel group design.

Furthermore, a limitation of our study was that quantitative measures (for example, nerve conduction studies, quantitative sensory thresholds) were not used to further characterise the type of neuropathy. Because of the heterogeneous nature of neuropathic pain in our study patients, we may not have identified a subset of patients who improved with gabapentin. Alternatively, the dosage of gabapentin may have been too low to induce analgesia in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy, although similar regimens have been reported to be effective in patients with other painful conditions.2 3

The results of this study suggest that gabapentin is probably ineffective or only minimally effective for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy at a dosage of 900 mg/day.